An Unmarked Grave, in Such Hallowed Ground

“May I suggest that the U.S. Marine Corps at your discretion Bestows the honor to this Revolutionary Hero by placing an appropriate marker in his honor in the Hallowed grounds of the Friends Society.

Honor Samuel Nicholas in all his due ceremony possibly on November 10th the official Birthday of the U.S. Marine Corps that his name is celebrated in the Annals of mankind.”

- John P. Tinneny to Commandant Leonard F. Chapman, Jr., January 16, 1968.

Gentlemen, Rebel, & Quaker

1744

Samuel Nicholas is born to prominent Quaker parents, Anthony and Mary Schute Nicholas, in Philadelphia. The family are members of the Monthly Meeting of Friends of Philadelphia (MMFP), the Quaker community that continues to worship at Arch Street Meeting House today.

Despite the spelling, Nicholas is actually pronounced as “nickels,” like the 5-cent coin.

1766

As a young adult, Nicholas establishes himself as a notable member of society and joins the Schuykill Fishing Company. Nicholas is a founding member of the Gloucester Fox Chasing Club, one of the first of its kind in the United States. Many of the club’s members later join the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry and serve in the Revolutionary War.

April 19, 1775

The American Revolutionary War begins with the battles at Lexington and Concord.

November 10, 1775

The Second Continental Congress raises two battalions of Continental Marines, and on November 28, 1775, John Hancock appoints Samuel Nicholas as the first commissioned officer.

Nicholas recruits five companies of marines with the help of friend and fellow officer, Robert Mullan, the proprietor of Tun Tavern.

December 5, 1775

Nicholas joins the Black Prince, a merchant ship built in Philadelphia and owned by Thomas Welling and Robert Morris. The ship was purchased by the Continental Congress on November 4, 1775, and outfitted for the Navy as a 24-gun frigate, later named the Alfred.

The work to convert the ship was extensive, and led by Philadelphia Quaker and shipbuilder Joshua Humphreys (1751-1838). Known as the Father of the American Navy, Humphreys designed the six original frigates of the Continental Navy. Of these frigates, the USS Constitution is still in use today.

March 1776

Captain Nicholas and Commodore Esek Hopkins sail aboard the Alfred and lead 284 men to Nassau for the Continental Marines’ first amphibious raid.

Little fighting ensued, as the attack the British troops were unprepared for the raid. The Marines captured 24 powder casks, 2 forts, 88 canons, 15 mortars, and a large number of other military stores and miscellaneous items. This is considered one of the most successful naval operations of the Revolutionary War.

June 25, 1776

Nicholas is promoted to Major of the Continental Marines.

July 1776

The minutes (records) of the Monthly Meeting of Friends of Philadelphia note that Maj. Nicholas accepts his removal from the Quaker community for his participation in the Revolutionary War. His wife, Mary Jenkins Nicholas, is later disowned by affiliation.

“The Meeting was informed that the testimony against Samuel Nicholas has been deliverd to him, and the acknowledged the rectitude of [friends] Judgment manifesting a comendable disposition of mind on ye occasion.”

- Minutes of the Monthly Meeting of Friends in Philadelphia, 1771-1777

Despite their high social standing, many members of the Nicholas & Jenkins family are disowned.

In the same records, Mary Gray Jenkins, Nicholas’s mother-in-law, has been asked to grant her enslaved servants their freedom, but she refused. At this time, Pennsylvania Quakers have embraced abolition and prohibited enslavement. Both Mary Gray Jenkins and Mary Nicholas continued to enslave Africans through at least the late 1790s.

1778

Nicholas marries local Quaker, Mary Jenkins, and becomes the proprietor of her family’s business, the Conestoga Wagon Inn. The Inn is still formally owned by Mary’s mother, Mary Gray Jenkins.

November 22, 1781

Samuel Nicholas retires from the Marines. By this time, his work had been primarily administrative, as he hadn’t seen combat in a few years.

Earlier this year, another Quaker meeting, the Religious Society of Free Quakers, was established.

Also called the Fighting Quakers, the Free Quakers worshiped at a new meetinghouse constructed in 1783 on 5th and Arch Streets. Among its worshippers are Betsy Ross, Timothy Matlack, and Samuel Wetherill.

April 1783

The Continental Marines are disbanded. Nicholas returns to life as a member of high society and proprietor of the Contestoga Wagon Inn.

1785

Maj. Nicholas serves on the Standing Committee of the State Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania until 1788.

August 27, 1790

Maj. Nicholas dies of an illness, presumably Yellow Fever, and is interred in an unmarked grave in the Friends Burial Ground at Arch Street Meeting House. It is unclear if he had repaired his relationship and been readmitted as a member of the Quaker meeting.

Mary Jenkins Nicolas continues to operate the Conestoga Wagon Inn.

July 11, 1798

President John Adams permanently reinstates the United States Marine Corps as a military force under the Department of the Navy.

April 19, 1805

After two years of construction, Arch Street Meeting House opens its doors for the first time.

This portrait of Samuel Nicholas was made by Maj. Donna J. Neary, USMCR, in 1989. To create it, she used another miniature painting of Maj. Nicholas, made by Charles Wilson Peale in the late 1770s.

Testimony of Peace

Quakers have lived according to the testimony of peace since the Religious Society of Friends’ earliest days in the mid-17th Century. Still, the Revolutionary War put this core belief to the test.

As the movement towards independence gained momentum in Philadelphia, many Quakers remained steadfast in their adherence to the pacifist tenet of nonviolence. They took a neutral stance by refusing to pledge allegiance to either the Patriot or the Loyalist cause.

The Revolution created deep divisions among Friends, and by 1785, over 1,700 Quakers were disowned or persecuted for supporting the War — either by directly taking up arms, providing supplies, affiliating with known participants, or other offences.

Samuel Nicholas was disowned from this Quaker community in July 1776.

Alfred at Anchor in Philadelphia, by William Nowland Van Powell, January 1, 1973.New Providence Raid, March 1776, by V. Zveg, 1973. US Naval History and Heritage CommandPictured here is an original Badge of the Cincinnati Medal.

Made of yellow gold and enamel in 1783 by Pierre Charles L’Enfant, this medal belonged to Maj. Samuel Nicholas and has been at the Metropolitan Museum of Art since 1935.

“It is strange indeed that such a heroic and capable figure faded quickly from view. It is the general belief among American historians that he died while comparatively a young man. Unfortunately, Marine Corps officials have never succeeded in finding any record of the death or burial place of the First Marine Officer.

The Marine Corps of today is greatly indebted to this gallant Quaker, who, armed in righteousness, established the prestige and the glory, that we are pledge to ‘carry on’.”

— The Leatherneck, 1927

The Lost Commandant

On January 16, 1968, John P. Tinnenney wrote a letter to Commandant Leonard F. Chapman, Jr., in Washington, D.C., recommending that the United States Marine Corps (U.S.M.C.) honors Samuel Nicholas with a memorial gravemarker and annual ceremony.

This inquiry sparked decades of correspondence and research by Marines, Quakers, and historians into the life and burial of the Continental Marines’ first and only Commandant.

Commandant Chapman responds to Tinneny’s request on February 5, 1969, sharing that they “…have been advised that it is against the policy of the Society of Friends to erect monuments on the grounds…where [Samuel Nicholas’] body is interred.”

Alice Allen, the Curator of Archives for Arch Street Meeting House, receives copies of these letters from Tinneny in January 1968 and begins to assist in his research. In her findings, Allen discovers Samuel Nicholas’ burial records for the very first time.

Later that year, on April 15, 1968, Allen was contacted by Edwin N. McClellan with additional research questions about Samuel Nicholas. They continue to write a series of letters sharing research findings and information until McClellan’s passing in 1971.

During the joint Monthly Meeting of Friends of Philadelphia and Central Philadelphia Monthly Meeting on November 15, 1973:

“..the Clerk [Sarah Yarnall] reported on phone conversations with Philip English, of the University of Pennsylvania ROTC, and with Dilworth Pierson of the [Philadelphia] Yearly Meeting Office, on the following matter. The founder of the Marine Corps, Captain [Nicolas], was a member of 4th & Arch Street Meeting, later disowned, but buried in the Meeting House grounds.

Every year, on November 10th at 10:00 a.m. the Marine Corps holds a memorial service which lasts about 15 minutes and includes some 15-20 people. The nature of the service is an honor guard with no weapons and no firing, a hand salute and the playing of Taps. They would like to hold his service in the courtyard of the Meeting House. They are aware of our stand on military matters and do not wish to offend anyone. The request would include making this an annual occurence.

This request discussed at some length with some Friends expressing strong feelings for, and others equally strong feelings agains, allowing this service to take place, while the ultimate decision rests with the Yearly Meeting, the position of this Meeting had been asked. Friends felt that all we could do was to report to Dilworth Pierson that there was no consensus within our Meeting.”

By November 18, 1973, conversations about hosting the Marines at the meetinghouse for an annual ceremony had come to a close—members of the Quaker meeting had not reached a consensus (they did not all agree), so the request was denied.

However, Marines and local Quakers continued to conduct research and share correspondence. On August 2, 1997, a group of twenty-five former Marines traveled to ASMH’s burial ground to pay their respects to Nicholas and all Marines who lie in unmarked graves.

On April 12, 1998, Paul L. Cathell, Jr., and Catherine “Cassie” Cathell wrote to Helen J. File, then Director of Arch Street Meeting House. The Cathells explain that they shared information about Nicholas with the 1st Marine Division Association and its Liberty Bell Chapter. They also wrote a short article in the U.S.M.C.’s Leatherneck Magazine.

Presumably penned by Paul, the letter describes how his initial interest in Samuel Nicholas was sparked by former Commandant Tom Rispoli, whom he spoke with at a flag-raising at Independence Hall on November 10, 1996. Commandant Rispoli mentioned that Nicholas’ unmarked grave was just a few blocks away at Arch Street Meeting House.

According to Cathall, “none of the Upland Detachment were aware of Commandant Nicholas’ burial site when [he] brought it to their attention.” This eventually led to the 1997 planned bus trip to Arch Street Meeting House with Commandant Rispoli and Garry Greenstein. Cathall made a VHS tape of the ceremony at ASMH and distributed it to any interested Marines.

By November 15, 1998, the request for a memorial marker had yet again reached the Meeting House:

“After thoughtful discussion, the meeting declined the request by the Marine Corps to place a grave marker for Samuel Nicholas, the first Commandant, because it is inconsistent with Friends’ peace testimony. It was also noted that there was no marker at the time of burial and no reason to change the tradition.”

With the memorial grave marker denied, conversations cease, and the Marines continue to hold their annual ceremony on November 10th. However, the Marines are persistent, and in September 2012, they asked for permission yet again:

“The Marine Corps League wants permission to install a permanent marker for Samuel Nichols, first commandant of the US Marines who is buried on the grounds…there was very little support for the concept among committee members and little encouragement should be given that such a request will actually be approved…” (MMFP Minutes, 2012)

By April 20, 2013, the Arch Street Meeting House Standing Committee records that “the Samuel Nicholas marker had been installed near the pink magnolia in the northeast ‘lawn’.”

Paul and Cassie Catthall shared an early design of the Samuel Nicholas memorial gravestone in 1998. They used another simple, Quaker-style, ASMH gravestone as a reference.

The memorial was still not approved for another fifteen years, but this design (typos excluded!) was eventually used.

John P. Tinneny (1916-1988) was born in Philadelphia and joined the Marines in 1934. After basic training at Paris Island, he worked as a military policeman at the Philadelphia Navy Yard until Spring 1935, when he was sent to China.

He served briefly in Shanghai and then with the mounted Marine Guard at the U.S. Embassy in Peiping. After the Marines left China, he was stationed at Cavite in the Philippines until the end of his four-year enlistment.

Image courtesy of Richard Tinneny.

Lieutenant Colonel Edwin N. McClellan (1881-1971) was the first director of the Historical Section of Headquarters, Marine Corps, now known as the Marine Corps History Division.

Birthplace of the Marines

Tun Tavern, or the Conestoga Wagon Inn?

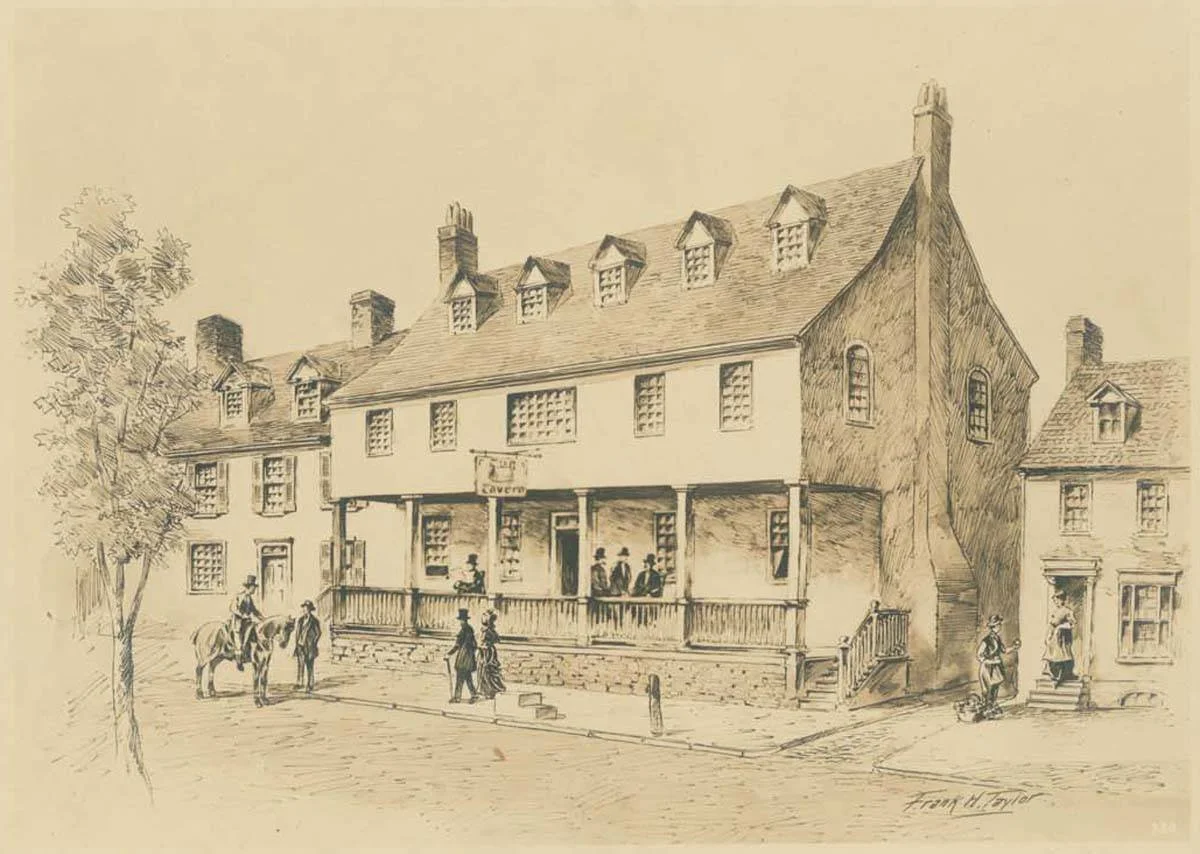

With the founding of the Continental Marines on November 10, 1775, Samuel Nicholas was commissioned as an officer and tasked with recruitment. Today, Tun Tavern is recognized as the primary recruitment location for the Continental Marines, but it may have begun at the Conestoga Wagon Inn.

Samuel Nicholas became the proprietor of the Conestoga Wagon Inn through his marriage to Mary Jenkins. The Inn was constructed in the early 1700s on High Street (now Market Street), between 4th and 5th Streets, as a stop along the Great Wagon Road through the colonies. Many notable figures, including some of our nation's Founding Fathers, visited the Conestoga Wagon Inn. Among them was George Washington, whose visit was documented in his diary on May 17, 1775.

In June 1776, Robert Mullan, a local businessman and friend of Samuel Nicholas, was appointed as Captain of the Marines. At the time, Mullan was the proprietor of Tun Tavern, one of the first and largest brew houses in Philadelphia. Most administrative work and meetings, such as officer rank assignments, took place at the Conestoga Wagon Inn, while recruitment primarily occurred at Tun Tavern due to its closer proximity to the wharf.

The preference for Tun Tavern as a recruitment site may have stemmed not just from its location but from Nicholas's desire to distance the family business from the controversies surrounding the Revolutionary cause. After all, it was considered treason. At this time, Nicholas was at odds with the local Quaker community, so limiting (or hiding) military activity at the Inn may have been an attempt to avoid social scandal.

After Nicholas retired from service, he continued his work as the Inn’s proprietor. Despite no longer being used as a meeting space for the Marines and their officers, the Inn remained an essential venue for local officials and the community. On May 25, 1787, the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia at the State House, now known as Independence Hall, and several delegates stayed at the Conestoga Wagon Inn.

When Nicholas passed in 1790, his wife, Mary Nicholas, continued to operate the Inn, as her family still owned it. Nicholas’ mother-in-law, Mary Gray Jenkins, passed away on June 23, 1797, and requested that the Conestoga Wagon Inn be sold. Josiah Harmar, Nicholas’ brother-in-law, purchased the Inn on September 19, 1798, but he likely did not operate it.

Like Tun Tavern, the Conestoga Wagon Inn no longer stands. These places and their patrons, while often forgotten, are quiet reminders of all who shaped our nation.